What is conflict analysis?

The verb analyze means to examine systematically or methodically by separating into parts and studying their interrelations. It basically means to break something down and study it carefully and in an orderly manner to discover how the parts work together. Analyzing a conflict means to “break” the conflict down and study it carefully to understand the actors, the conflict’s biography, its causes, and its dynamics. Conflict analysis is the process of analyzing a conflict so that we can understand the conflict well enough to bring about a conflict transformation.

Some definitions

- According to Matthew Levinger, “Conflict analysis a structured inquiry into the causes and potential direction of a conflict. It seeks to identify opportunities for managing or resolving disputes without recourse to violent action” (Levinger, n.d.).

- Conflict analysis has also been defined as “the systematic study of the profile, causes, actors, and dynamics of conflict” (Nicaise, n.d).

- “Conflict analysis refers to the systematic study of conflict in general and of individual or group conflicts in particular. It provides a structured inquiry into the causes and potential flight of a conflict so that processes of resolution can be better understood” (USlegal.com).

- “Conflict analysis is the deliberate study of the causes, actors, and dynamics of conflict” (Woodrow 2012).

My definition

For our study, borrowing elements from the above definitions, I define conflict analysis as “the systematic study of the ABCDs of a conflict to identify life-giving opportunities for transforming the conflict.”

ABCD is a mnemonic I created that stands for Actors, Biographical account/profile, Causes, Dynamics. Another useful mnemonic I created for the same thing is PACE, which stands for Profile, Actors, Causes, and Evolution.

Some key things to know about conflict analysis

- Conflict analysis is a systematic study of the ABCDs of conflict.

- Just as physicians have to perform a thorough history and physical examination together with necessary labs and imaging to analyze and understand a disease condition before prescribing treatment, Peace practitioners engage in conflict analysis to diagnosis a conflict situation before developing programs to transform the conflict.

- A cooperative approach to conflict goes through the same general phases that a physician would undergo to treat a patient. This involves: “(1) diagnosing the conflict, (2) identifying alternative solutions, (3) evaluating and choosing a mutually acceptable solution, and (4) committing to the decision and implementing it” (Weitzman 2014, 203-229). Conflict analysis plays a crucial part in helping us handle the first phase of diagnosing the conflict so that the subsequent treatment phases can be successful.

- Conflict analysis should first be done individually and then when possible in a participatory manner within a group.

- “Conflict analysis is not an ‘objective’ art” (Mason & Rychard, n.d.). Conflict analysis is subjective. Our perception and interpretation of what is going on within a conflict are shaped by our paradigms or worldviews — as such, analyzing a conflict “does not lead to an objective understanding of the conflict” (Mason & Rychard, n.d.). Instead, it makes our subjective perceptions transparent. It’s been said that thoughts unravel when they pass through the lips or the tips of the fingers when you write. Analyzing a conflict allows us to reflect on our perceptions and communicate them clearly. Keeping in mind that conflict analysis is not a wholly objective activity should help one be humble about their own views and respectfully consider the views of others.

- Conflicts are dynamic; they are continuously changing. As such, intervention that is done to the conflict becomes part of the conflict. As such, every intervention should focus on helping transform the conflict and bring about constructive change.

- Conflict analysis is not a one-time event. You continue to revisit and reanalyze to make sure that the causes, etc. are considered.

- Conflict analysis views conflict as a system.

- Conflicts occur within a context that should be analyzed with that context in mind. The context affects the conflict but is itself separate from it.

- Conflict is a nested phenomenon. “Every conflict is a sub-system in a larger system – its context (or super-system). A conflict in one sub-system may only be a symptom of a conflict located in the “context” of a larger system” (Mason & Rychard, n.d.).

- Conflict analysis should include, at least, an analysis of the people, problem, and process.

- Three illustrative metaphors of conflict are an iceberg, tree, and an earthquake (epicenter vs. focus).

- As you analyze conflict, remember that conflict never occurs in a vacuum. Every conflict has a story to tell anyone who would listen. Every conflict has a history or a biography. Conflict always grows within a soil (environment). The social structures and systems within which we live (e.g., political, economic, religious, organizational–both local and global) and the cultural context (both local and global) within which we live are often in the background of conflict. As Maire Dugan noted, conflict is nested and occurs within a social setting or system (Dugan 1996, 9-20). Trying to isolate the conflict from the social environment and social systems that gave rise to the conflict will not help to transform the conflict.

- Conflict stages help us understand and analyze conflicts.

- “Conflict analysis should be distinguished from context analysis—which seeks to understand the broader situation, including all economic, social, and political factors. The conflict exists within the context and is influenced by it, but the conflict has its own important dynamics” (Woodrow 2012).

- Conflict analysis involves 1) Checking to see if an issue meets our definition of a conflict, 2) Understanding the nature of conflict as a nested phenomenon and applying that knowledge to understand a particular conflict, 3) Defining the conflict system and its boundaries and key features (actors, etc), and using a conflict analysis tool to understand and organize information about the conflict (Mason & Rychard, n.d.).

Some worldviews that influence conflict analysis include:

- The Positions vs. Interest view: This view holds that conflicts can be easily resolved when the parties instead of focusing on their positions (what people say they want), focus on interests (why people want what they say they want).

- Basic human needs view: This view believes that conflicts occur when fundamental human needs are not satisfied. This view advocates joint problem-solving that analyzes and addresses fundamental human needs as a means of dealing with conflict.

- The Conflict Transformation view: The conflict transformation paradigm sees conflict as an opportunity for constructive change. It seeks to address deep-rooted causes of conflict and not only stop something bad but start something new and good. Conflict transformation is contrasted to conflict resolution, which conflict transformation proponents view as not far-reaching enough to transform the conflict for good.

Tools for Conflict Analysis

There are many tools that can be used to analyze a conflict. Below are three common tools:

- Onion Actor Tool: Allows you to analyze the actors in a conflict –their positions (what people say they want), interests (what they really want), and needs (what they must have).

- Conflict Tree: A conflict tree allows you to analyze the issues (core problems) in a conflict to visualize the causes and effects of each issue. It uses a tree diagram with the roots (representing the root causes), trunk (core problem), and the branches (effects).

- The INVESTIGATOR framework: INVESTIGATOR is a mnemonic for performing a thorough conflict analysis. You will learn more about it below.

1. Onion Actor Analysis

The onion tool allows you to analyze the actors (or stakeholders) in a conflict–their positions (what people say they want), interests (what they really want), and needs (what they must have). To use the onion tool, draw three concentric circles, as in the Mexico example below. You can either draw two separate sets of three concentric circles, one for each party, or you can use one set of concentric circles as in the example from Mexico below, and draw a line in the middle. Use one side for one party and the other side for the other party. Write positions (in the outer circle), Interests in the middle circle, and Needs in the inner circle. Again, see the example below.

Note: The onion actor analysis requires two parties because each conflict has at least two actors or parties. You have to know not just your own needs, interests, and positions but seek to understand also those of your opponent. Understanding both parties’ needs, interests, and positions by effective analysis allows you to enter into a negotiation prepared to transform the conflict and do effective joint problem solving to address the interests and needs of both parties.

Also, note that the needs in an onion actor analysis, and all conflicts, refer to the fundamental human needs that each of us has. As you analyze the other actor, show great empathy. You need to see the other person as a human being and enter into their shoes and see the world as they do. This doesn’t mean that you have to agree or endorse the way they view things. You just need to understand it from their perspective. Then state their needs, interests, and positions with respect in such a way that if they were to read it and be honest with themselves, they will say, “that’s right.” Don’t represent them in a way that makes them evil. Most of the time, humans in conflict are doing what they see as best and fighting to defend what they think is right. It’s rare to see a human being who is just all evil and motivated by pure evil. The light of God still shines in our hearts, even in our darkest moments. It’s best to always assume the best about the intentions of the other party in a conflict.

E.g., Onion actor analysis ‒ actors’ positions, interests, and needs in Chiapas, Mexico

Source: gsdrc.org/topic-guides/conflict-analysis/core-elements/

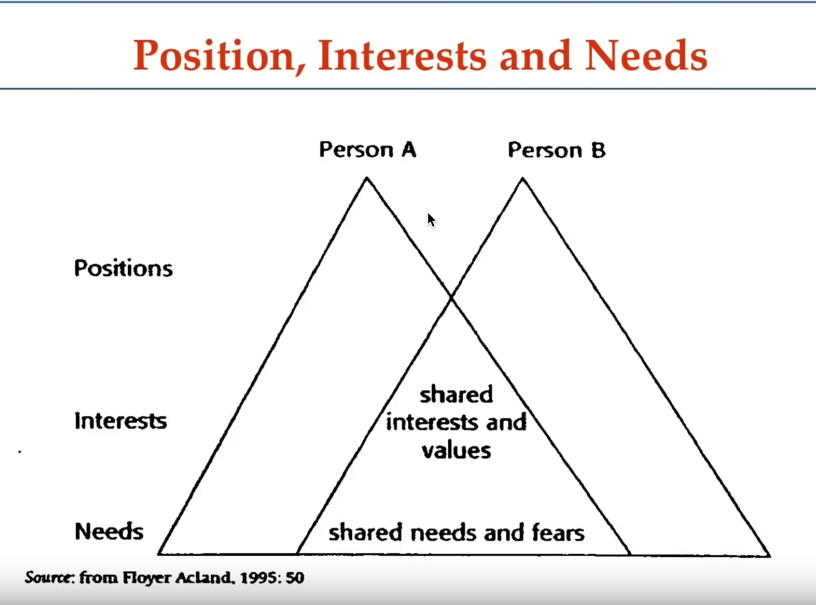

Using triangles, as shown below, is another way of analyzing the same three elements analyzed using the onion actor tool.

from prof P. K. Shajahan, Tata Institute of Social Sciences

2. Conflict Tree Issue Analysis

A conflict tree allows you to analyze the issues (core problems) in a conflict to visualize the causes and effects of each issue. The Conflict Tree works with one issue (core problem) at a time and helps us to tease out the root causes, and the effects of the issue (Woodrow 2012). Depending on the conflict, “it can serve as an initial step in preparation for later steps of analysis, such as systems mapping.” (Woodrow 2012).

On a board (black or white) or a large piece of paper, draw a tree with the roots (root causes), trunk (core problem), and the branches (effects).

Next, start by writing the core problem (or issue) on the stem of the tree and then work out the corresponding causes (roots) and the effects of that core problem. Your core problem or issue needs to be very specific. I once had a student identify the issue on their conflict tree as “marital problems.” That’s very vague and general. It’s like saying there are “national issues” when a country is at civil war or when two countries are at war, you name the issue, “international problems.” Lots of issues between a wife and husband can be categorized as marital problems. E.g. If a wife is cheating on a husband, that’s a marital problem. You can go on and on with examples of marital problems. The issue needs to be specific. The more specific the better. If a doctor’s diagnosis of a disease is vague and general, e.g. aches, it’s hard to go off with that to determine a specific cause and treatment. Is it aches in the chest, abdomen, head, toes, fingers, hand, shoulder, back? In the case of aches, even going to the level of saying it’s backache is not enough. The diagnosis has to be even more specific than that to say, e.g. musculoskeletal back pain or sciatica or cancer, etc. The list of things that can cause backache is long. You can check it here for acute back pain. The more specific the diagnosis of the issue, the easier it is to come up with the right roots and effects. The same is true for issues in a conflict. To ensure you have a specific issue, you could apply SMART to your issue to make sure it is specific, measurable, audacious (in terms of radical transparency), realistic, and time-bound.

The conflict tree exercise is best done in a collaborative setting with a group of people or in a workshop. It’s recommended to use this tool individually and then as a group of people affected by the conflict. When working on the conflict tree in a group setting where the tree is drawn on a large board, for example, one could give everyone sticky notes on which to write what they perceive as the causes and effects of a chosen issue or core problem. See the example below. The advantage of using sticky notes is that they can be easily moved around as the group becomes clear about what information should go where.

Remember to start with identifying a core problem (or specific issue), and then identifying its root causes and effects.

The conflict tree allows us to assess the structural and systemic issues that are often the root causes of conflict.

Check out the following steps for carrying out a conflict tree activity from conflict analysis resource funded by the Norwegian Church Aid.

E.g., Conflict tree to visualize conflict causes in Kenya

Source: gsdrc.org/topic-guides/conflict-analysis/core-elements/

3. The INVESTIGATOR Framework

Dr. Christopher Mitchell (Professor Emeritus of Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University) was one of the early practitioners in the field of conflict analysis and created a mnemonic called SPITCEROW for analyzing key aspects of a conflict. SPITCEROW stands for Sources, Parties, Interests, Tactics, Change over time, Escalation, Resources, outcomes, and Winners in the conflict.

I have remixed and upgraded SPITCEROW to INVESTIGATOR. When you look up the meaning of investigator in a dictionary, you will see that an investigator is a person who investigates, such as a detective or private investigator. To do conflict analysis well, you need to put on your INVESTIGATOR hat and mind. From a conflict transformation perspective, conflict provides an opportunity for constructive change. When you analyze a conflict, you acting as an investigator who studies the conflict like a crime scene to understand it. You are searching for an understanding of the conflict that will allow you to transform the conflict and create something better in its place than was there before. That’s why I prefer INVESTIGATOR to SPITCEROW. Even though conflict analysis isn’t pure science, those doing it must try to be as objective as possible. The conflict analyzer must become an investigator.

I have remixed and upgraded SPITCEROW to INVESTIGATOR. When you look up the meaning of investigator in a dictionary, you will see that an investigator is a person who investigates, such as a detective or private investigator. To do conflict analysis well, you need to put on your INVESTIGATOR hat and mind. From a conflict transformation perspective, conflict provides an opportunity for constructive change. When you analyze a conflict, you acting as an investigator who studies the conflict like a crime scene to understand it. You are searching for an understanding of the conflict that will allow you to transform the conflict and create something better in its place than was there before. That’s why I prefer INVESTIGATOR to SPITCEROW. Even though conflict analysis isn’t pure science, those doing it must try to be as objective as possible. The conflict analyzer must become an investigator.

INVESTIGATOR stands for the following:

- I-Interests vs. positions: Positions are what people say they want, and interests are why they want what they want. Some practitioners define interests as the “preferred way to get one’s needs met; interests are the desires, concerns, and fears that drive the position” (Woodrow 2012).

- N-Needs: Needs are the basic human physical, psychological, and social, requirements for life that underlie interests. What needs are behind each party’s interests and positions? See fundamental human needs.

- V-Values: What are the values of each party?

- E-Escalation and Effects: How has the conflict escalated (evolved)? What are the effects of the conflict?

- S-Sources (structural, etc.): What are the origins or sources of the conflict? The sources of the conflict can be divided into remote vs. immediate sources or ultimate vs. proximate sources.

- T-Triggers: What are the immediate triggers of the conflict?

- I-Issues (problems): What are the issues or points of disagreement between the parties?

- G-Goals: What are each party’s goals? “In conflict situations, ‘goals’ can be defined as desirable future conditions that

originally motivate the partisans to contest with each other. While tangible goals may include territorial, political, and economic advantages, less tangible goals involve prestige, honor, and respect” (Jeong 2008, 24). - A-Actors (parties/people): Who are the actors involved in the conflict, and how did they get involved? Is anybody winning?

- T-Tactics: What tactics and strategies are being used by the parties? What forms of behaviors or tactics are the adversaries using against each other?

- O-Outcomes: What was the eventual outcome of the conflict? What is the desired outcome of the conflict?

- R-Resources: What quantifiable resources are people disputing over? E.g., a dispute over the way funds are allocated within an organization; A dispute over property rights or boundaries in a neighborhood right. Resources here refers to material needs or things that are quantifiable.

In this lecture by Susan Allen Nan, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University, she recommends going through each of the points on SPITCEROW (INVESTIGATOR) with each of the parties and asking them what they see as sources, Parties, Interests, Tactics, Change over time, Escalation, Resources, outcomes, and winners in the conflict.

In my research for this lesson, I’ve seen different authors use different versions of the acrostic SPITCEROW. This is common with mnemonics as different authors like most elements of another person’s work but choose to modify it slightly to suit their context. I’ve chosen to use a new word altogether.

Here is an example of a conflict analyzed using SPITCEROW or INVESTIGATOR.

Bibliography

Dugan, Maire. “A Nested Theory of Conflict.” A Leadership Journal: Women in Leadership – Sharing the Vision 1 (July 1996), 9-20. https://emu.edu/cjp/docs/Dugan_Maire_Nested-Model-Original.pdf.

Jeong, Ho-Won. Understanding Conflict and Conflict Analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2008. https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2015/MVZ208/um/59326109/Ho-Won_Jeong_Understanding_Conflict_and_Conflict_Analysis_2008.pdf.

Levinger, Matthew, Conflict Analysis: Understanding Causes, Unlocking Solutions, at https://www.usip.org/publications/conflict-analysis-questions-and-answers-author, Last Accessed 2/5/2020

Mason, Simon, and Sandra Rychard. “Conflict Analysis Tools Tip Sheet.” Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. Accessed February 9, 2020. https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/Conflict-Analysis-Tools.pdf.

Nicaise, Guillaume, http://www.guillaumenicaise.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/resum%C3%A9-du-cours_analyse-de-conflits.pdf, Last Accessed 2/5/2020

Weitzman, Eben A., and Patricia Weitzman. “THE PSDM MODEL Integrating Problem Solving and Decision Making in Conflict Resolution.” In The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed., 203-229. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Woodrow, Peter. “Conflict Analysis Framework.” Norwegian Church Aid. Last modified May 2012. https://www.kpsrl.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/363_conflict_analysis_framework_field_guidelines.pdf.

https://definitions.uslegal.com/c/conflict-analysis/ Last Accessed, Jan 9, 2015